A Wail in the Darkness: Investigating the Enduring Legend of La Llorona

Is the Weeping Woman a tragic ghost, a vengeful goddess, or a reflection of our own deepest fears? We follow the chilling evidence behind the Americas' most haunting tale.

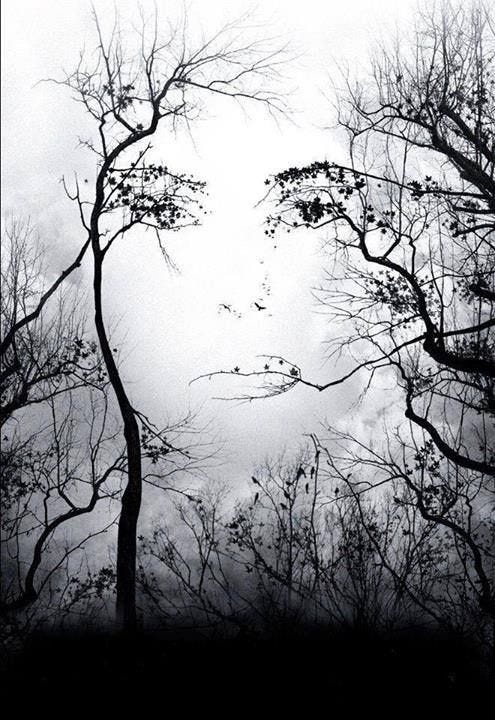

It’s one of the most persistent sounds in all of American folklore - a woman’s cry in the darkness near a river. ¡Ay, mis hijos! The lament is famous, but it’s the chilling details within the lore that make it so deeply unsettling. For centuries, the stories have included a strange, paradoxical rule about the sound: if the wail seems far away, the spirit is terrifyingly close. If it sounds near, she’s at a distance. It’s an acoustic anomaly that turns the simple act of listening into a potential trap.

This is the signature of La Llorona, the Weeping Woman. Her story is so deeply woven into the fabric of the Americas that it feels less like a ghost story and more like a piece of living history, an omen that has echoed for half a millennia.

And this is where the story gets truly fascinating. The simple tale of a grieving mother is just the beginning. When you start to trace that wail back in time, you realize it’s not just one story. It’s a 500-year-old echo that connects to Aztec goddesses, the violent birth of a new culture during the Spanish Conquest, and real historical events that fueled the legend. It seems the ghost everyone thinks they know is just one piece of a much larger, more complex puzzle.

The Legend & Lore: The Tale of Endless Tears

Before we delve into the deep historical currents, we must start with the story itself. It’s a powerful narrative, and its core elements are remarkably consistent wherever it’s told.

The tale usually begins with a woman named Maria, who was said to be exceptionally beautiful but came from a humble background. Her pride, however, was anything but humble. Her beauty eventually attracted a man of a much higher social and racial class - often a wealthy Spanish nobleman or a rich ranchero. They began a passionate affair, and she bore him two sons.

For a time, they were happy. However, eventually, the man’s obligations to his status prevailed. He abandoned Maria and their children, planning to marry a woman from his own elite social circle. His old family was now just an inconvenient secret.

Blinded by a furious, all-consuming rage, Maria took her children to the river and, in a single, horrific act, she drowned them. The moment the deed was done, the rage vanished, replaced by an overwhelming guilt that shattered her sanity. She died on that same riverbank, and her spirit was stained by her crime. Denied peace, she was cursed to wander the waterways for eternity, trapped between this world and the next. Her entire existence is now defined by her grief and her ceaseless, wailing search for the children whose lives she took. This is the source of her iconic cry, “¡Ay, mis hijos!” (“Oh, my children!”).

And the legend doesn’t end with her suffering. It’s a cautionary tale because, in her madness, the Weeping Woman is said to snatch living children who wander too close to the water, tragically mistaking them for her own lost sons.

Historical Context: A Ghost Forged in Trauma

To find the origins of La Llorona, you have to dig. Way back. Before the Spanish, before the ghost story, and into the very cosmology of the Aztec Empire.

The Pre-Hispanic Foundation: A Crying Goddess

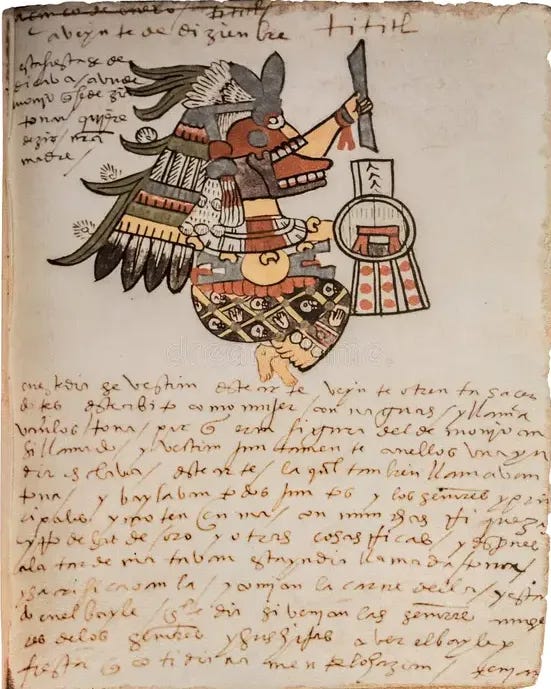

Long before she was a ghost, the wailing woman was a goddess. The most significant precursor to La Llorona in the Aztec Pantheon is Cihuacoatl, the “Snake Woman.” She was a powerful earth goddess, deeply associated with motherhood and childbirth. According to the 16th-century Florentine Codex, which recorded accounts from Náhuatl-speaking witnesses, a weeping woman was heard in the streets of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan ten years before Cortés even arrived. This was considered the 6th omen foretelling the empire’s doom. But she wasn’t crying for a lost lover; she was Cihuacoatl, wailing for the impending destruction of her people. Her cry was a collective one: “Oh my children, we are about to go forever,” or “Oh my children, where am I to take you?”.

The connections don’t stop there. Cihuacotl was the patroness of the Cihuateteo, the feared spirits of women who died in childbirth. These spirits were known to haunt crossroads at night to steal living children. The link between a wailing female spirit and child abduction was already there. Add to that the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue, “She of the Jade Skirt,” the ruler of all water. She had the power to drown people, and ceremonies in her honor sometimes involved child sacrifice, providing the legend’s essential connection to water and drowning.

The Trauma of Conquest: A National Allegory

The Spanish Conquest of the 16th century was a cataclysmic event that left a deep and lasting trauma on a national scale. In this storm of violence and cultural erasure, the wailing goddess was reshaped into a powerful allegory for the vanquished nation.

This is where the historical figure of La Malinche (also known as Malintzin or Doña Marina) enters the picture. A Nahua woman, she served as Hernán Cortés’s interpreter, advisor, and concubine, and she bore his son. She is one of the most ambivalent figures in Mexican history - seen by many as both the symbolic mother of the new mixed-race (mestizo) people and a traitor who helped bring about the ruin of her own. The legend of La Llorona became fused with her story. In this powerful interpretation, the Weeping Woman is the indigenous mother betrayed by her Spanish lover (Cortés), left to weep for her mestizo children, who were now caught between two worlds, dispossessed of their heritage.

A Colonial Crucible: The Real-World Tragedy

The ghost story we know today was forged in the rigid social hierarchy of the Spanish colonial period. This society was built on a racial caste system, or limpia de sangre (“cleanliness of blood”), that prized European heritage above all else. The common narrative of the legend—a poor indigenous or mestiza woman abandoned by a wealthy white Spaniard—is a direct reflection of the stark power imbalances of this era.

This historical context provides a chillingly plausible, non-supernatural basis for the legend’s core tragedy. Historians note that as more Spanish women arrived in the colonies, the status of the indigenous and mestiza women who had first formed unions with Spanish men declined sharply. It became a common practice for the mestizo children of these unions to be taken from their indigenous mothers to be raised as “Spanish,” effectively severing them from their maternal culture. This real-world history of forced dispossession provides a concrete foundation for the story of a mother’s unending grief. The legend thus evolved into a powerful cautionary tale, warning of the fatal dangers of transgressing the rigid racial and class boundaries of colonial society.

Eyewitness Accounts: Echoes Across Centuries

The history gives the legend its weight, but the ghost story lives and breathes through the people who claim to have witnessed her. From 16th-century omens to 21st-century Reddit posts, the volume and consistency of the accounts are staggering. When you start to synthesize them, a chillingly consistent profile of the Weeping Woman begins to emerge.

The Historical Composite

The first “official” account of a wailing woman dates back to the years just before the Spanish conquest (c. 1509-1519). Recorded in the Florentine Codex, it was described as the 6th great omen foretelling the Aztec empire’s doom: a woman was heard weeping and shouting in the streets of Tenochtitlán at night, crying, “Oh my children, we are about to go forever.”

From that primal scream, centuries of folklore have built a composite sketch of the entity.

Her Appearance: She is almost universally described as wearing a white gown, which is often reported as looking wet or tattered. She is a tall, thin, ethereal figure who seems to float or glide rather than walk. The true terror lies in her face, which is often obscured by long, dark hair or a veil. In accounts where it’s seen, it’s rarely human; witnesses describe a fleshless skull, empty eye sockets, or, in one of the most bizarre and frightening variations, the head of a horse.

Her Wail: The defining characteristic is her supernatural cry, a lament for her children: “¡Ay, mis hijos!” (“Oh, my children!”). It’s considered a harbinger of misfortune or even death. Witnesses also report the chilling paradoxical proximity of the sound - if her cries sound distant, she’s actually very close, and if they sound near, she’s far away. Her approach is often preceded by another sound: the sudden, frantic, and terrified barking of dogs.

The Mid-Century Urban Shift

The idea that La Llorona is a purely rural legend is a mistake. In a landmark 1968 study, “La Llorona in Juvenile Hall,” folklorist Bess Lomax Hawes documented the story as a living tradition among young Mexican Americans in Southern California. She found the legend adapting to new urban environments, with the spirit being associated not just with rivers, but modern dangers like car crashes. This showed that La Llorona’s territory evolves, anchoring itself to new places of tragedy and danger.

Modern Encounters in the Digital Age

The tradition of sharing these encounters continues today, often moving from oral tradition to online forums. These anecdotal accounts show how the legend endures.

El Paso, Texas: One user on Reddit shared an experience from their childhood, waking up at 4 AM to a “horrible screaming” coming from a ditch near their trailer home. They described it as sounding like a woman “screaming her guts out down a big hallway.” Another user from the El Paso area described seeing a “person but all white and kinda translucent” in an empty field behind their home late at night, noting that on some nights, the air feels “heavy” and even their dogs hurry back inside.

San Antonio, Texas: The area around Woman Hollering Creek, just outside San Antonio, is a well-known hotspot for La Llorona activity. One particularly harrowing story posted on Reddit’s r/nosleep recounts a father and child’s “Llorona hunting” trip. The terrifying encounter involved a hand pressing against the car window and a voice repeating “Mi hija” (“My daughter”), followed by the sounds of someone trying to crawl through the broken window after the father fired his pistol in a panic.

Quindio, Colombia: A recent story from 2025 on Reddit’s r/Ghoststories illustrates La Llorona’s adaptation to technology. A family living near a river reported hearing a soft, pained, human-like weeping. The true terror came when an ambulance arrived at their home at 1 AM, responding to a distress call that no one in the house had made. Local lore suggests that La Llorona has learned to use modern tools, such as phones, to lure people or gain entry to a home.

A Radical Reinterpretation

Perhaps one of the most startling modern takes comes from parapsychologist Christopher Chacon. After reportedly investigating over 2500 eyewitness accounts, Chacon concluded that while the phenomenon was real in many cases, the malevolent legend was a lie. He asserts that in the credible encounters, the entity was benevolent and protective towards children. Chacon posits that the original story was a fabrication by an abusive husband to cover up his own act of infanticide, a lie that has been perpetuated for centuries. This theory reframes La Llorona not as a monster, but as the ghost of the first victim, forever tied to the scene of the crime.

Investigating the Mundane: The Skeptic’s Inquisition

While the stories are compelling, a critical examination reveals that the legend of La Llorona also functions as a profound cultural and psychological construct. This analysis doesn’t seek to diminish the experiences of witnesses, but rather to understand the human and societal functions that have given the story such incredible vitality for centuries.

The Psychological & Sociological Lens

From a functionalist perspective, the legend serves clear and powerful roles within the societies that tell it.

A Tool for Social Control: At its most basic, the story is a cautionary tale designed to enforce social norms. For children, she is a “bogeyman” figure, a terrifying reason to obey parents and, crucially, to stay away from the very real dangers of rivers and irrigation ditches. For adults, the legend traditionally policed behavior along strict gender lines, warning women against perceived sins like vanity and premarital sexuality, while cautioning men about the consequences of infidelity.

An Archetype of Trauma: Psychoanalytic interpretations see La Llorona as an embodiment of deep-seated human emotions and traumas. She gives voice to the darker aspects of motherhood—grief, sacrifice, and the immense pressure placed upon mothers. More recent interpretations explicitly connect her tragic actions to the silent suffering of postpartum depression, reframing her from a monster into a victim of an unacknowledged mental health crisis.

A Symbol of Resistance: In a striking reversal, feminist and postcolonial theories analyze the legend as a site of cultural resistance. Chicana feminist scholars reclaimed the figure, shifting focus from her “sin” to the systemic oppression - colonialism, racism, and patriarchy - that drove her to a desperate act. In this empowered reading, her wail transforms from a cry of passive grief into a grito (a powerful shout) of rage and defiance against injustice.

The Rationalist Lens: Explaining the “Encounter”

For those who report a direct, personal encounter, science offers several explanations rooted in psychology and perception.

Auditory & Visual Pareidolia: This is a well-documented psychological phenomenon where the brain perceives meaningful patterns in vague or random stimuli. It’s a leading candidate for explaining many ghostly encounters. The mournful wail of La Llorona could be the mind’s interpretation of the natural sounds of wind howling through trees, the rustling of leaves, or the gurgling of river water. Similarly, a fleeting glimpse of a tall, white figure in the dark could be the brain imposing a human shape onto mist, a strangely shaped tree, or shifting shadows.

Misidentification: In low-light conditions, it’s easy to misidentify known animals. The unsettling, mournful calls of certain nocturnal birds, like some species of owl, have been suggested as a possible source for the “wail.”

Known Psychological States: Certain altered states of consciousness can produce vivid sensory experiences. These include hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations - vivid, dream-like auditory or visual hallucinations that occur as a person is falling asleep or waking up. Another is sleep paralysis, which can be accompanied by a strong sense of a menacing presence and frightening hallucinations.

These rational explanations are powerful and could account for many of the stories. But can they explain everything? Can they account for the sheer consistency of the sightings across centuries and cultures, or the highly specific, bizarre details - like a horse’s head or paradoxical acoustics - reported by multiple, unconnected witnesses? While science and psychology offer plausible alternatives, they don’t entirely silence the woman who weeps by the water. The question of what, precisely, people are experiencing remains stubbornly, fascinatingly open.

The Weeping Never Stops

So where does that leave us? We started with a wail in the dark and ended up deep in the history of a continent. We’ve seen how the Weeping Woman is far more than a simple ghost. She is a figure of incredible complexity, a story that has been shaped and reshaped over the past 500 years.

She began as a goddess, Cihaucoatl, and omen of collective doom for the Aztec people. In the fires of the Spanish Conquest, her story was forged with the trauma of a nation and the identity of La Malinche, becoming a potent allegory for betrayal and cultural loss. In the centuries that followed, she became the tragic ghost we know today, a cautionary tale built on the very real social injustices of the colonial era. And today, she continues to evolve. For some, she is a symbol of feminist rage and social protest against modern violence, for others, she remains a terrifyingly real presence, an active phenomenon with new encounters being reported in our own time.

Is she a ghost? A cultural memory? A psychological archetype for our deepest fears about grief and motherhood? Or simply a story we tell to explain the unexplainable sounds in the night? The unsettling answer may be that she is all of these things at once. She’s a powerful narrative that feeds on history and tragedy, but she is also a phenomenon that, for many, is frightenly real. The rational explanations are plausible, yet they don’t quite manage to silence her.

The next time you’re near a quiet body of water at night, listen closely. Is it just the wind, or something more?

If this investigation gave you chills, consider sharing Paranormal Pathways with a friend who loves a good mystery. And if you want to make sure you never miss a deep dive into the strange and unexplainable, be sure to subscribe. We’re just getting started.

References

Acosta, C. M. (2021). La Llorona, Picante Pero Sabroso: The Mexican Horror Legend as a Form of Communication [Master's thesis, Western Kentucky University]. WKU TopSCHOLAR. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/3501/

Addis, Y. H. (2019). The Wailing Woman: "La Llorona", A Legend of Mexico. Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers, 1(2), 131-136.

Alexander, K. (2025, January). La Llorona - Weeping Woman of the Southwest. Legends of America. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/gh-lallorona/

Anaya, R. (n.d.). The Legend of La Llorona. In EBSCO Research Starters: Literature & Writing. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/literature-and-writing/legend-la-llorona-ru

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

Arrizón, A. (1998). Mythical Performativity: The Body as Site of Writing and Ritual. In V. L. Martínez & G. M. Padilla (Eds.), The Woman, the Writer, and the Indian. University of California Press.

Bustamante, J. (Director). (2019). La Llorona [Film]. La Casa de Producción.

Candelaria, C. (1980). La Malinche, Feminist Prototype. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 5(2), 1-6.

Carbonell, A. M. (1999). From Llorona to Gritona: Coatlicue in Feminist Tales by Viramontes and Cisneros. MELUS, 24(2), 53-74. https://doi.org/10.2307/467699

Carpio, M. (1849). La Llorona. In Poesías del Sr. Dr. Don Manuel Carpio.

Chacon, C. (n.d.). As cited in La Llorona: The Legend, the Reality. Latin Heat. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://latinheat.com/la-llorona-the-legend-the-reality/

Cohen, J. J. (1996). Monster Culture (Seven Theses). In J. J. Cohen (Ed.), Monster Theory: Reading Culture (pp. 3-25). University of Minnesota Press.

Duarte, G. (2006). La Llorona's Ancestry: Crossing Cultural Boundaries. In K. Untiedt (Ed.), Folklore: In All of Us, In All we Do. University of North Texas Press.

Esquivel Suárez, M. (2021). A Country Full of Lloronas: La Llorona as a Protest Symbol Against Enforced Disappearances in Mexico [Master's thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland]. https://research.library.mun.ca/15174/1/thesis.pdf

Florez, C. (2012). La Llorona, the Indian Woman, and the Spanish Soldier: A Postcolonial Reading of a Family Legend. Utah State University. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=honors

Fuller, A. (2017, October 31). The Wailing Woman. History Today. https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/wailing-woman

Hawes, B. L. (1968). La Llorona in Juvenile Hall. Western Folklore, 27(3), 153-170.

Hayes, J. (1987). La llorona = The weeping woman: an Hispanic legend. Cinco Puntos Press.

Janvier, T. A. (1910). Legends of the City of Mexico. Harper & Brothers.

Kearney, M. (1969). La Llorona as a Social Symbol. Western Folklore, 28(3), 199-206.

Kirtley, B. F. (1960). "La Llorona" and Related Themes. Western Folklore, 19(3), 155-168.

León-Portilla, M. (Ed.). (1992). The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico (L. Kemp, Trans.). Beacon Press. (Original work published 1959)

Lockhart, J. (Ed. & Trans.). (1993). We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. University of California Press.

Morales, O. (2010). La Llorona as a symbol of resistance. Unpublished manuscript.

Nelson, P. (2008, May). Rewriting Myth: New Interpretations of La Malinche, La Llorona, and La Virgen de Guadalupe in Chicana Feminist Literature. CORE. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/235417597.pdf

Paz, O. (1950). The Labyrinth of Solitude. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Perez, D. R. (2008). There Was a Woman: La Llorona from Folklore to Popular Culture. University of Texas Press.

Perez, D. R. (2012). The Politics of Taking: La Llorona in the Cultural Mainstream. The Journal of Popular Culture, 45(1), 153-172.

Powers, K. V. (2000). Women in the Crucible of Conquest: The Gendered Genesis of Spanish American Society, 1500-1600. University of New Mexico Press.

Radford, B. (2014). Mysterious New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

Ramírez Rodríguez, S. M. (2008). Stepping Away From the River: La Llorona as a Symbol of Female Empowerment in Chicano Literature. https://scholar.uprm.edu/bitstreams/928c6623-a293-484c-83b6-bd9217ed385d/download

Rivera, R. R. (1883). La Llorona: cuento popular.

Sahagún, B. de. (ca. 1577). Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España (The Florentine Codex). World Digital Library. https://www.wdl.org/en/item/10096/

Serrano, S. (n.d.). As cited in La Llorona: Critical Analysis. Cited at the Crossroads. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://citedatthecrossroads.net/chst332/2014/04/17/33-la-llorona-critical-analysis/

Townsend, C. (2003). Burying the White Gods: New Perspectives on the Conquest of Mexico. The American Historical Review, 108(3), 659-687.

Townsend, C. (2006). Malintzin's Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

Trujillo, P. (n.d.). As cited in La Llorona: Folklore, Spirits, Colonialism, and Power. Retrospect Journal. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://retrospectjournal.com/2019/11/03/la-llorona-folklore-spirits-colonialism-and-power/