Frame 352: The Enduring Mystery of the Patterson-Gimlin Film

For 57 years, 954 frames of grainy 16mm film have defied debunking. Is it the zoological discovery of the century or the most successful hoax ever pulled off?

Some moments in history are so strange, so loaded with possibility, that they get burned onto a single strip of film. For the JFK assassination, it’s the Zepruder film. For the world of paranormal investigation, it’s 59.5 seconds of shaky 16mm celluloid shot in the deep woods of Northern California on October 20, 1967. This is the Patterson-Gimlin film, and it’s without a doubt the undisputed cornerstone of modern Bigfoot lore.

Before this footage, the creature we call Bigfoot was a collection of whispers, Indigenous accounts, and mysteriously large footprints left in the mud. It was a campfire story. But for 954 frames, it became something else entirely. It became a physical presence.

And at the heart of that presence is one, single, iconic moment.

Out of the entire frantic clip, it’s this fraction of a second that everyone remembers. The creature, mid-stride, turns its entire upper torso in a fluid, powerful motion to cast a look back at the men filming it. There’s no panic in the gesture. It’s an unhurried, almost dismissive glance before it continues walking and disappears into the forest.

That single look is what elevates the footage from a simple monster sighting into a genuine enigma. For over half a century, that footage has been analyzed by everyone from FBI forensic labs and Hollywood special effects wizards to university primatologists and passionate amateur sleuths. And after all that time, we are no closer to a definitive answer. The film has stubbornly resisted every attempt to conclusively debunk it, yet the circumstances of its creation are so suspicious that they practically scream “hoax.”

So, what are we looking at? Is this the zoological discovery of the century, frozen on grainy color film? Or is it the most successful and enduring campfire story ever told? Let’s break down the tape, examine the evidence, and see if we can finally get to the bottom of what really happened that day at Bluff Creek.

The 59 Seconds That Created a Legend

The encounter at Bluff Creek wasn’t an accident. It was the culmination of a quest, driven by the relentless obsession of a man named Roger Patterson.

Patterson was a former rodeo rider from Yakima, Washington. His fascination with Bigfoot ignited after he read a 1959 article in True magazine. This wasn’t a casual hobby; it became a full-blown fixation. He led multiple expeditions into the Bluff Creek area, which had been a hotspot for discoveries of large, unidentified tracks since 1958. By 1966, his passion was so consuming that he self-published his own book on the subject: Do Abominable Snowmen of America Really Exist?.

But expeditions cost money, and Patterson was short on funds. He turned to Bob Gimlin, a fellow horseman, for help. Gimlin, a “real-deal cowboy,” was not a believer at first. He was skeptical of his friend’s pursuit but was eventually persuaded to join him. When Patterson heard reports of new tracks found by a logging crew in October 1967, he convinced Gimlin it was time to go. They loaded three horses into Gimlin’s truck and headed for the Six Rivers National Forest, armed with a rented 16mm Cine-Kodak K-100 camera. Their stated goal was simple: find proof.

According to their accounts, they found it on the afternoon of Friday, October 20th. They were riding upstream along Bluff Creek when, as they rounded a bend, the horses suddenly panicked. Less than 100 feet away, they saw it: a large, bipedal, ape-like figure walking along the creek bed.

The scene was pure chaos. Patterson’s horse fell, and he scrambled to untangle himself and yank the movie camera from his saddlebag. He then ran toward the creature while trying to film, which explains the shaky, frantic quality of the first few frames. The resulting footage captures the subject as it strides across a sandbar. Patterson closed the distance from about 120 feet to roughly 80 feet as he steadied his shot. Then came the iconic moment - the creature, mid-stride, turned its upper body to glance back before continuing its unhurried retreat into the woods.

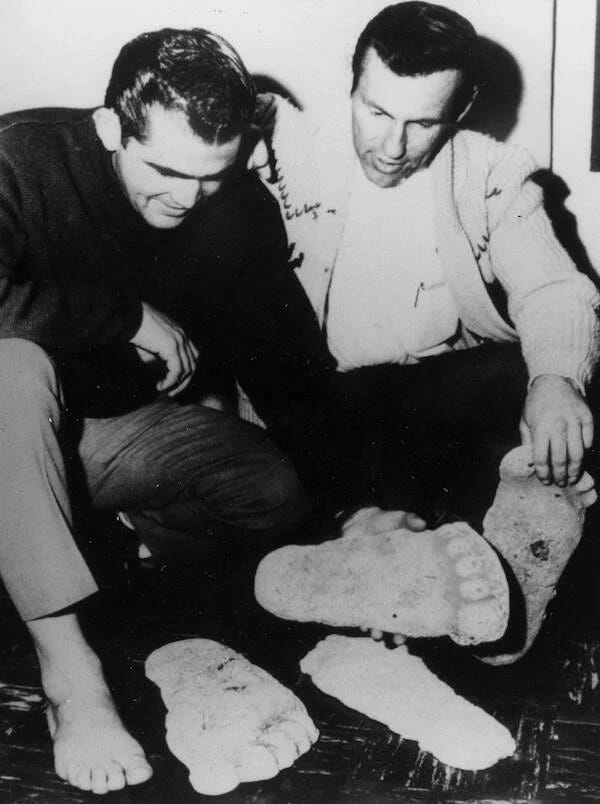

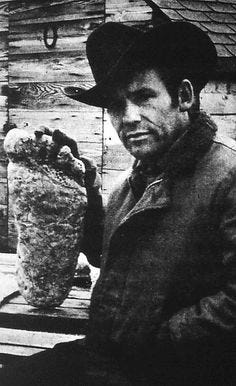

In the immediate aftermath, the men reported a lingering, “skunky, rank odor.” After calming their horses, they got to work making plaster casts of the creature’s footprints. The prints were massive, measuring 14.5 inches in length.

Patterson’s next moves showed a clear intent to go public. He and Gimlin rode 30 miles to a store, where Patterson called the Times-Standard newspaper in Eureka. He also arranged to ship the undeveloped film to his brother-in-law for processing. The story broke with astonishing speed. The very next day, the front page of the local paper ran the headline: “Mrs. Bigfoot is Filmed!”. With those words in print, the footage from Bluff Creek was on its way to becoming a worldwide phenomenon.

The Case for Authenticity: Flesh and Blood, Not Fabric and Foam

The arguments against the Patterson-Gimlin film often boil down to a simple assumption: it’s just a man in a suit. But for proponents, that’s where the problem begins. They argue that the sum of the visual details captured in those 954 frames adds up to a level of “irreproducible complexity” - something that seems far beyond what a simple costume, or even 1967’s most advanced special effects, could achieve.

The Impossible Gait

The first and most enduring argument for the film’s authenticity has always been the creature’s walk. It just doesn’t move like a human. Proponents argue that “Patty” displays a “compliant gait” that’s fundamentally different from our own. Watch the film closely: the knee remains bent throughout the entire stride, even when bearing the creature’s full weight, while the body leans forward, creating a fluid, powerful, rolling motion.

Could an actor do that? Biomechanics experts claim it would be extraordinarily difficult to fake, especially while wearing a cumbersome suit on the uneven, sandy ground of a creek bed. The creature’s calculated walking speed of approximately 3.85 mph is also notably faster than the average human walking speed of about 3.1 mph.

Then there’s the foot itself. Some analysts claim to see evidence of a “midtarsal break,” a flexibility in the middle of the foot just like an ape’s. Modern humans don’t have that; our feet evolved into rigid arches to support our weight. It’s a subtle, non-human detail that adds another layer of complexity to the creature’s strange, yet seemingly effortless, locomotion.

Anatomy of an Unknown Primate

The case for a living, breathing animal goes deeper than just the way it walked. When analysts digitally stabilize the shaky footage, details emerge that proponents say defy the simple “man-in-a-suit” explanation. The most compelling of these is the appearance of muscle.

Proponents like anatomy professor Jeff Meldrum argue that as the creature walks, you can actually see the movement of large muscle groups beneath its hairy coat. They point to the bulging and contracting of what appear to be the quadriceps, deltoids, and trapezius muscles, all moving in a way that seems consistent with a powerful biological entity. The question they pose is a simple one: Is that just the awkward bunching of a cheap costume, or is it the dynamic flexion of living tissue?

Other anatomical details also complicate the hoax theory. The figure clearly has large, pendulous breasts, which is what led to the nickname “Patty” and the argument that this was a female of an unknown species. Beyond that, some researchers have argued for the presence of a sagittal crest—a bony ridge on the top of the skull common in male great apes and some extinct hominins. While this feature is heavily debated even among believers, the suggestion that the creature displays specific, complex primate anatomy moves the conversation far away from a simple gorilla suit bought from a costume shop.

Beyond 1967 Technology

This brings us to the final, crucial argument. If it were a suit, who on Earth could have made it?

Consider the timing. Patterson filmed his creature in October 1967. Just four months later, the landmark film Planet of the Apes hit theaters. That movie featured the most advanced primate costumes Hollywood could create, and they even won an honorary Oscar for the achievement. For most people, that was the peak of special effects.

However, when some effects experts put the two side by side, the comparison is startling. It’s all about the details. The ape costumes in the movie, while groundbreaking, were still clearly suits. They were built on fabric, which caused them to bunch and fold unnaturally at the knees and elbows. The fur often had a uniform, carpet-like texture.

The creature in Patterson’s film is different. Proponents, such as Hollywood effects veteran Bill Munns, point to the way its “skin” seems to flex and how the hair has a natural sheen and variable length, like real animal fur. Most importantly, they argue that the creature shows dynamic muscle definition. The muscles in the thigh, back, and shoulders appear to contract and relax as it walks. That’s something that wasn’t possible with the static foam-and-fabric techniques of the day.

This leaves a powerful, lingering question. If Hollywood’s best, with massive budgets and teams of artists, couldn’t create something this convincing, how could a broke rodeo rider from Yakima have pulled it off?

Proponents say the answer is simple.

He didn’t.

The Case for a Hoax: A Monster of Circumstance

The arguments for the film’s authenticity are powerful. They force us to question the limits of technology and the possibility of unknown species. But the case against the Patterson-Gimlin film has almost nothing to do with muscle flexion or compliant gaits. For skeptics, the entire story falls apart long before you ever look at a single frame. They argue that the whole thing is a monster of circumstances.

The Man with the Motive

The investigation into the hoax theory begins and ends with one man: Roger Patterson. While his supporters view him as a dedicated seeker who got lucky, skeptics paint a much darker picture. They point to his well-documented financial struggles and his reputation in his own community as a “conman” and a “known grifter.” Patterson was a man with a clear and powerful monetary motive to produce a sensational piece of evidence.

Then there are the circumstances of the encounter itself, which skeptics find profoundly suspicious. Patterson wasn’t just some random camper who got lucky. He had already published a book on Bigfoot. He was also actively trying to fund a docudrama about hunting the creature. He arrived at Bluff Creek armed with a rented movie camera, specifically for this purpose.

And then, he happens to stumble upon a perfect subject, walking through a clearing, in broad daylight.

Was it the luckiest break in the history of cryptozoology? Or was it a well-planned scene, staged by a man who desperately needed it to be real? For skeptics, the answer is obvious.

The Men in the Suit?

A motive is one thing. But a hoax needs a method. For decades, the biggest question for skeptics was: if it was a man in a suit, who was the man, and where did the suit come from? The story got a lot more specific in the late 1990s, when two different men came forward with answers.

The first was Bob Heironimus, a laborer from Yakima and an acquaintance of Patterson. In a series of interviews, he publicly claimed he was the man inside the suit. His story was detailed. He alleged that Patterson offered him $ 1,000 to wear a costume for the film, although he was never actually paid. He even described the suit itself: synthetic fur and horsehide, bulked up with football shoulder pads, with a modified football helmet for the headpiece.

But there’s a big problem. His story had holes. For example, Heironimus initially claimed the filming took place near Yakima, a fact that is easily disproven. The site was definitely located at Bluff Creek, hundreds of miles away. With his primary witnesses being close family members, his credibility took a major hit.

Heironimus provides a potential actor. But what about the costume itself? That’s where Philip Morris enters the picture. In 2002, Morris, a costume and magic-prop designer, added another layer to the hoax theory. He claimed that in the summer of 1967, he sold a $435 gorilla suit to Roger Patterson. Patterson allegedly told him he needed it for a “rodeo act.” According to Morris, Patterson later called him asking for advice on how to make the suit look more realistic.

It seems like a perfect fit. But Morris’s story has its own issues. He admitted that the distinctive conical head and the pendulous breasts seen in the film were not part of his standard suit. This means Patterson would have had to perform significant and skillful modifications on his own.

These two accounts give the hoax theory a tangible shape. But the inconsistencies in their stories have kept them from being the slam-dunk proof that skeptics were hoping for.

The Scientific Rejection

The stories from the alleged hoaxers are messy and full of contradictions. The verdict from mainstream science? Not so much. From the very beginning, the scientific community has overwhelmingly rejected the Patterson-Gimlin film as evidence of an unknown primate.

One of the first and most influential voices was John Napier, a respected primatologist from the Smithsonian Institute. After a thorough analysis, he delivered a crushing conclusion. He declared the film to be a “brilliantly executed hoax.” Napier argued that specific features, like the creature’s gait and the “hourglass” shape of its footprints, were inconsistent with those of a real, large primate.

More broadly, this rejection gets at the heart of how science works. The scientific community classifies cryptozoology as a pseudoscience. Why? Because it generally starts with the conclusion that a creature exists and then searches only for evidence to support that belief. That’s the opposite of the scientific method, which creates a testable hypothesis that can be proven false.

For science, the ultimate and insurmountable obstacle is the total lack of conclusive physical proof. Despite more than 50 years of searching since the film was shot, no bodies, bones, teeth, or scientifically verified DNA samples have ever been recovered. For scientists, the bottom line is simple: no body, no Bigfoot.

The Enduring Debate: The Technology of Ambiguity

We’ve reached an impasse. On one side, we have a piece of film showing something that experts, even today, can’t easily explain. On the other, we have a mountain of suspicious circumstances, questionable characters, and a flat-out rejection from mainstream science.

So why can’t we get a definitive answer? The truth is, the film’s greatest strength is its greatest weakness: its technical quality.

The combination of a shaky, handheld camera, grainy 16mm film stock, and the brief window of clear footage creates what some have called a “sweet spot of ambiguity.” It’s clear enough to be tantalizing, but just blurry enough to resist a final verdict. Adding another impossible layer of difficulty is a crucial fact: the original camera film has been missing since the 1980s. Every analysis you’ve ever seen is a copy of a copy, each generation adding its own new flaws and artifacts.

Modern technology has turned the film into a digital Rorschach test. Proponents use stabilization and enhancement software to reveal what they see as clear muscle flexion. Skeptics argue that this same process merely creates digital noise, encouraging our brains to see patterns that aren’t really there—a phenomenon known as pareidolia.

This creates a fundamental clash of evidentiary standards. The two sides aren’t just disagreeing; they’re arguing from two completely different starting points.

The Proponent’s Stance: The visual evidence in the film is extraordinary. The burden of proof is on skeptics to find a zipper or perfectly replicate the footage.

The Skeptic’s Stance: The circumstantial evidence of a hoax is overwhelming. The burden of proof is on believers to overcome Patterson’s character and the sheer implausibility of the encounter.

They aren’t just arguing over different conclusions. They’re arguing from different philosophies about what counts as valid evidence. It’s an impasse that has ensured the Patterson-Gimlin film remains a perfect, perpetual mystery.

The Pact

So where does that leave us?

We’ve picked apart the film frame by frame. We’ve heard from the experts, the believers, and the skeptics. We’ve dug into the life of the man behind the camera. And after all of it, we’re left right where we started: staring at a grainy figure as it turns to look back at us.

The case remains perfectly split. On one hand, you have the story of a living creature. Its anatomy and movements have defied definitive debunking for over half a century. On the other hand, you have the story of a desperate man with a history of schemes who may have created an ingenious, perfectly timed hoax. Both accounts are compelling. Both have major holes.

This is the source of the film’s power. It exists in a state of perfect tension. Its legacy is a pact between what the footage shows and the deep suspicion surrounding how it was made. It offers just enough to make you want to believe, but not enough to ever be certain. It’s a pact between ambiguity and possibility.

The Patterson-Gimlin film did more than just capture an image; it gave a face and a form to countless footprints and fireside stories. It tapped into the ancient “wild man” archetype that has long haunted the North American psyche and presented it to a modern world that was ready to question authority and believe in the unbelievable.

So what did Roger Patterson capture in the frame that day? A monster, or a man in a suit?

The film offers no final answer. The creature simply turns, looks back, and walks away.

What's Your Verdict?

So, what do you think? After weighing all the evidence, where do you land—biological creature or brilliant hoax?

The deepest conversations happen in our comments section, which is an exclusive feature for our paid members. If you're a paid subscriber, head down there now and let me know your take. Was Roger Patterson lucky or a liar?

If you're a free subscriber and this investigation has you hooked, consider upgrading to join the debate and unlock our full archive of case files. Either way, sharing this article with a friend who loves a good mystery is one of the best ways to support our work!

References

Bartholomew, R. E., & Regal, B. (2009). The Man-Monkey Myth: A Case Study in the Science of Pseudoscience. In The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus Books.

Byrne, P. (1975). The Search for Big Foot: Monster, Myth or Man?. Acropolis Books.

Coleman, L. (2003). Bigfoot!: The true story of apes in America. Simon and Schuster.

Daegling, D. J. (2004). Bigfoot exposed: An anthropologist examines America's enduring legend. Altamira Press.

Green, J. (2006). Sasquatch: The Apes Among Us. Hancock House Publishers.

Hayes, F. E. (2022). The Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot film reconsidered: Is the proof out there? ResearchGate. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363350640_The_Patterson-Gimlin_Bigfoot_film_reconsidered_is_the_proof_out_there

Korff, K. K., & Kocis, M. (2004). Exposing Roger Patterson's 1967 Bigfoot film hoax. Center for Inquiry. Retrieved from https://cdn.centerforquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/2004/07/22164653/p35.pdf

Long, G. (2004). The Making of Bigfoot: The Inside Story. Prometheus Books.

Loxton, D., & Prothero, D. R. (2013). Abominable Science!: Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids. Columbia University Press.

Meldrum, J. (2007). Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science. Forge Books.

MonsterQuest. (2010, February 3). Bob Gimlin - The Last Witness (Season 4, Episode 7) [TV series episode]. History Channel.

Munns, B. (2014). When Roger Met Patty. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Murphy, C. (2012). The Patterson/Gimlin film: Some noteworthy insights. Relict Hominoid Inquiry, 1, 71-86.

Napier, J. R. (1973). Bigfoot: The Yeti and Sasquatch in myth and reality. E.P. Dutton.

Nickell, J. (2011). Tracking the Man-Beasts: Sasquatch, Vampires, Zombies, and More. University Press of Kentucky.

O'Connor, J. (2024). Tracking Bigfoot. Boston College Magazine.

Patterson, R. (1967). Interview on The 7 O'Clock Show. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

Prothero, D. R. (2015, September 12). Bigfoot Skepticism (No. 535) [Audio podcast episode]. In S. Novella (Host), The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe.

Radford, B. (2017). Bigfoot at 50: The Enduring Legacy of the Patterson-Gimlin Film. Skeptical Inquirer, 41(5), 26-28.

Rosman, J. (2017, December 20). Film introducing Bigfoot to world still mysterious 50 years later. OPB.

Sagers, A. (2022, October 20). The Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot film is still unexplained 55 years later. Den of Geek.

Schmitt, D. O. (1985). A Biomechanical Assessment of the Upright Bipedal Locomotion of a Hominoid. Journal of Human Evolution, 14(3), 269-278.

Schrader, K. (2016, July 5). The man who created Bigfoot. Outside Online.

Shermer, M. (2003). The Bigfoot Film Controversy. Skeptic Magazine, 10(4).

Souder, W. (2021, March 19). The Enduring Legend of Bigfoot. The Wall Street Journal.

Wallace, R. (1967, October 21). Mrs. Bigfoot Is Filmed! The Humboldt Times-Standard.

Way, D. (2023, August 21). The true story of the Patterson-Gimlin film that some say proves Bigfoot is real. All That's Interesting.