"The Call is Coming from Inside the House": The Terrifying True Crime Behind America's Most Famous Urban Legend

For over 60 years, the story of the tormented babysitter has been a fixture of American nightmares. The truth behind the legend, however, is far more disturbing.

You know this story.

Even if you’ve never heard it told around a campfire, you know it. It’s a piece of psychic malware that was installed in the American consciousness decades ago. It’s a script that runs in the background of our culture, a self-contained nightmare that feels both ancient and chillingly immediate.

The details are always the same. A teenage girl is babysitting for the first time at a new house. The kids are asleep upstairs. The house is big, quiet, and full of the unfamiliar groans and settling sounds of a strange place. She’s watching TV, trying to relax, when the phone rings. It’s a landline, of course. A solid, physical object tethered to the wall.

The first call is a hang-up. Annoying, but whatever. A wrong number. The second call is just silence on the other end, an unnerving dead air that makes the hair on her arms stand up. She hangs up, a little faster this time.

The third call is when the voice appears. It’s a man, his voice a low, gravelly whisper. “Have you checked the children?” he asks.

She slams the phone down. This isn’t a prank anymore. Her heart is a frantic drum against her ribs. She runs to the front door, checks the deadbolt, draws the curtains. But the house feels different now. The silence isn’t empty anymore; it feels like it’s listening. The calls keep coming, each one more specific, more personal. He asks what she’s wearing. He describes the movie she’s watching. He’s not just calling; he’s watching.

Finally, she calls the operator for help. In some versions, it’s the police. The voice on the other end is calm, professional. They can trace the call, but she has to keep him on the line for at least sixty seconds. It’s an eternity. When the phone rings again, she picks it up, her hand slick with sweat, and listens to the man’s taunts, her eyes locked on the clock. She manages a full minute before she throws the receiver back into its cradle.

It rings again, almost immediately. It’s the operator, but the professional calm is gone, replaced with a raw adrenaline-spiked panic.

“Get out of the house! We’ve traced the call… It’s coming from inside the house!”

That final line is a system shock. It’s a conclusion that weaponizes the very idea of safety. The researcher Jan Harold Brunvand pointed this out back in the 80s - the true horror is the sudden, gut-wrenching realization that the monster isn’t trying to break down the door.

He’s been inside the whole time.

A script this powerful doesn’t just fade away. It embeds itself in the culture. It gets passed down, retold, and relived. But its persistence is only half of the anomaly. The other half is its specificity.

A narrative this detailed, with this exact sequence of events, feels eerily familiar. It feels less like something invented and more like something remembered. Like a distorted echo of a real scream, on a real telephone, on a real night, a long time ago.

From Whisper to Scream: A Nightmare Goes Viral

A terrifying story today can flash across the globe in seconds. But this particular script had to travel the hard way, through a world wired with copper and connected by paper. Its journey from hushed rumor to a national cautionary tale is a masterclass in pre-Internet contagion. To track its path is to follow a signal as it finds its way out of the static, jumping from one medium to the next until it was broadcasting everywhere.

The Analog Network

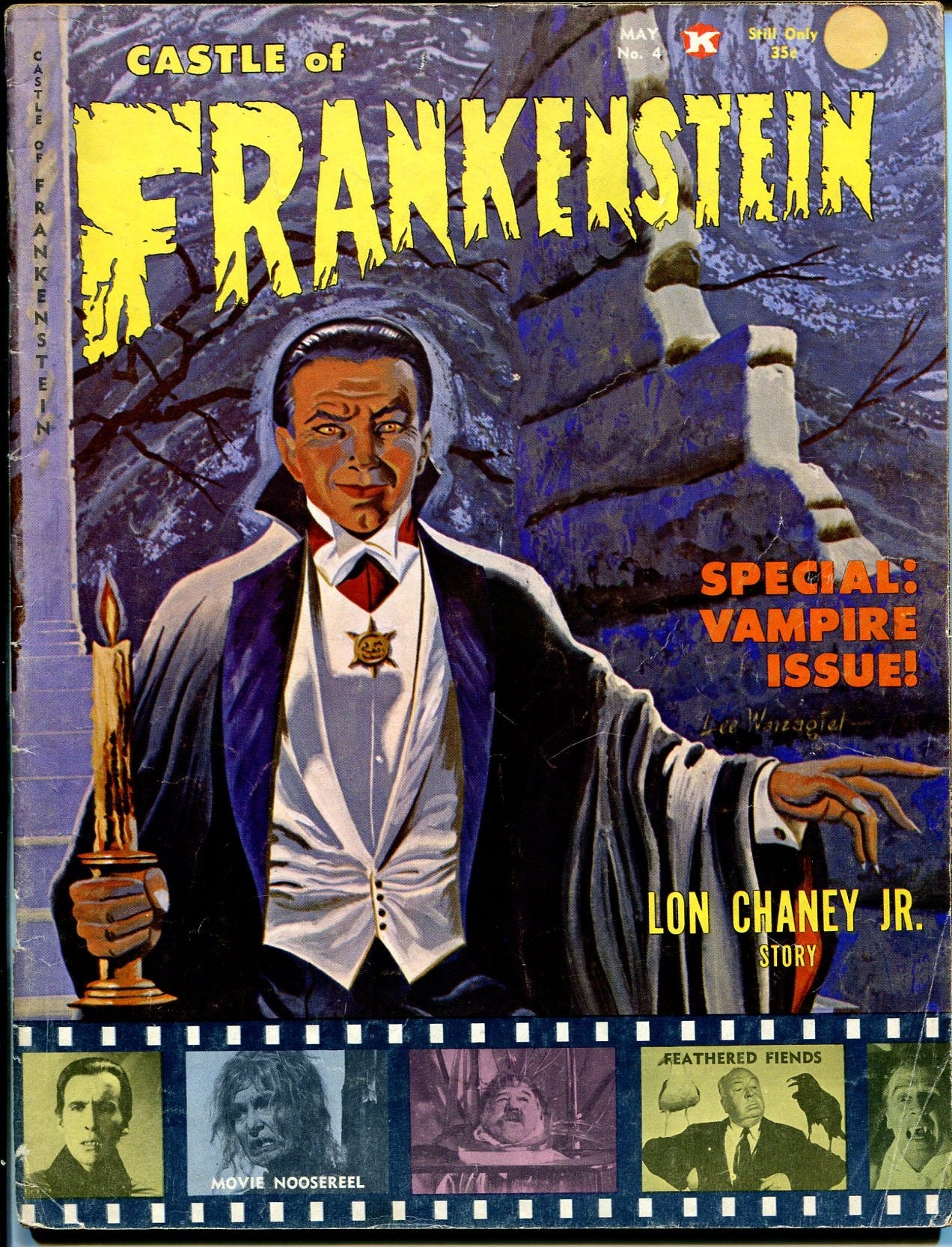

To find the first physical trace of this narrative, you have to dig into the archives of the weird. You have to go looking in the pulpy, ink-stained pages of a 1964 monster movie fanzine called Castle of Frankenstein.

This was the horror underground of its day, a magazine for people who obsessively traded trivia about creature features and gothic chillers. And right there, in its fourth issue, someone submitted the whole, terrifying sequence, titled simply “The Babysitter.” The calls, the panic, the operator, the final reveal—it was all there. Finding this is like an archaeologist unearthing a key artifact. It’s the fossil record, proving the story was already fully formed and spreading through a grassroots network of horror fans.

From that shadowy corner of pop culture, the script began to bleed into the mainstream. Throughout the 1960s, a strange phenomenon started cropping up in the advice columns of Dear Abby. People from all over the country were writing in with a palpable sense of urgency, describing this horrifying story they’d heard and asking a simple question: Is this real?

They were treating the account as credible intelligence, a genuine news report about a clear and present danger that they needed to confirm.

And that’s where the signal gets a massive boost. This thing escaped the horror fan bubble and mutated, landing on the breakfast tables of mainstream America. People writing into Dear Abby were treating it like an FBI warning, a clear and present danger they needed to confirm. The script was evolving from a scary story into a piece of battlefield intel for surviving modern life.

The Hollywood Broadcast

A story circulating in the underground is one thing. But for a script to achieve true cultural saturation, it needs a bigger platform. In the 1970s, Hollywood became that amplifier, taking this raw, terrifying signal that was spreading through the analog network and blasting it out to the entire world.

Hollywood, of course, smelled blood in the water. The first to really weaponize the script was Bob Clark’s 1974 film, Black Christmas. It isn’t a direct retelling of the babysitter story, but it’s built on the same terrifying engine: a sorority house gets besieged by these unhinged, violent phone calls from an unseen man. The film’s horrifying climax reveals that the killer has been making the calls from inside the house the whole time. That movie proved this one core idea was absolute nightmare fuel for an audience, and you can basically draw a straight line from the reveal to the entire slasher genre that followed.

Five years later, the definitive version hit theaters. The opening twenty minutes of Fred Walton’s 1979 film, When a Stranger Calls, is a beat-for-beat, nerve-shredding dramatization of the script that had been circulating for years. There’s no ambiguity here. In a 2017 interview for the film’s Blu-ray release, Walton confirmed that his only goal for that opening was to perfectly capture the scary story he, and millions of others, had heard growing up. He took the whispered nightmare and projected it onto the big screen in full, terrifying color. That act cemented the script into our cultural DNA, burning into our collective memory with a single line of dialogue:

“Have you checked the children?”

Anatomy of a National Nightmare: The Real Fears that Fueled the Story

A story like this doesn’t become a monster on its own. It needs the right environment to grow—a culture primed with specific anxieties it can feed on.

The babysitter script became so powerful because it wasn’t whispering into a void. It was plugging directly into a set of very real, very raw nerves in mid-century America. Before we can even look at the specific crimes that might have inspired it, we have to understand the background radiation of fear that was already making people check their locks at night.

The Wire in the Wall: Terror by Telephone

The telephone was supposed to be a miracle. It was a lifeline, a tool that could conquer distance and summon help in an instant. It connected isolated farmhouses to the rest of the world and gave suburban families a new sense of security.

But every miracle has a shadow.

As this technology wove its way into the fabric of daily life, a deeply unsettling side effect began to emerge. The same wire that brought the voices of loved ones into the home could also bring the voice of a predator.

This created a brand-new kind of violation. And almost immediately, people began to exploit it.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, a genuine social panic began to spread concerning obscene and harassing phone calls. Newspapers and magazines from the era are filled with accounts of women, in particular, being targeted by anonymous callers who used the privacy of the telephone to threaten and terrorize.

The raw material for this nightmare was already there, pulsing through the phone lines of mid-century America. A documented crime wave of harassing and obscene calls was genuinely terrorizing people, mostly women, in their homes. The babysitter script simply took that widespread, ambient dread and gave it a face. It packaged the real-world fear of the anonymous caller into a single, unforgettable narrative that felt less like fiction and more like a confirmed report.

A Climate of Fear: The True Crime Wave that Haunted America

The anxiety wasn’t just coming through the phone lines. It was staring back from the front page of every newspaper. A series of brutal, seemingly random crimes had shattered the post-war sense of American security, creating a national climate of fear that the babysitter script fit into like a key in a lock.

These weren’t stories. They were headlines.

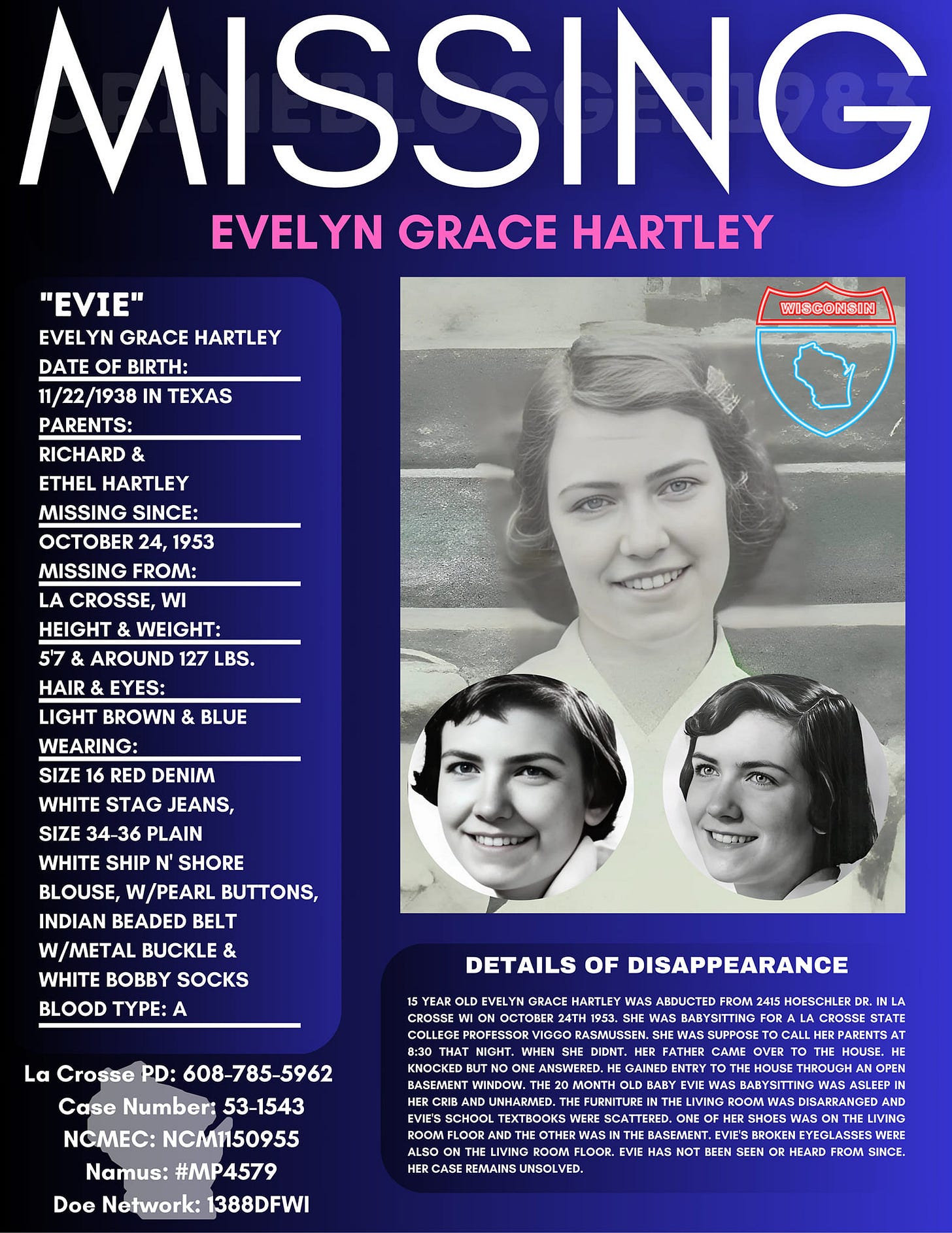

On October 24, 1953, in La Crosse, Wisconsin, a 15-year-old babysitter named Evelyn Hartley vanished. She was watching the children of a university professor when she disappeared. The scene left behind was a carbon copy of a future nightmare: signs of a violent struggle, a slashed window screen, and furniture in disarray. Her glasses and schoolbooks were left behind. Evelyn was never seen again.

The Hartley case became a national obsession. It screamed a terrifying message across the country: the girl-next-door, left in charge of a home, was not a guardian. She was a target.

The idea of the “vulnerable babysitter” solidified into a real, documented fear, ripped straight from the headlines.

And it wasn’t just the babysitters. The very sanctity of the home was under assault. On November 15, 1959, the Clutter family was murdered in their remote farmhouse in Holcomb, Kansas. The crime, later immortalized in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, was a cultural earthquake. It single-handedly demolished the sacred American belief that a locked house in the middle of nowhere was a safe haven.

If a family could be slaughtered in their own beds for no reason, was anywhere truly safe?

This background radiation of real-world horror created the perfect conditions for the babysitter script to thrive. The narrative thrived by absorbing the most terrifying elements of the evening news—the vulnerable guardian, the violated home, the unseen predator—and weaving them into one perfect, unforgettable story.

The Archetype: Inside the Janett Christman Case File

The widespread fear in mid-century America was the perfect fuel for a nightmare, but fuel needs a spark. A story as specific as the one about the babysitter doesn’t just materialize from a vague cultural anxiety. It needs a blueprint. It needs a real-world event with a sequence of events so potent and precise that it could serve as a dark origin story. After digging through regional archives, it seems the blueprint was drafted in a quiet college town in the American heartland.

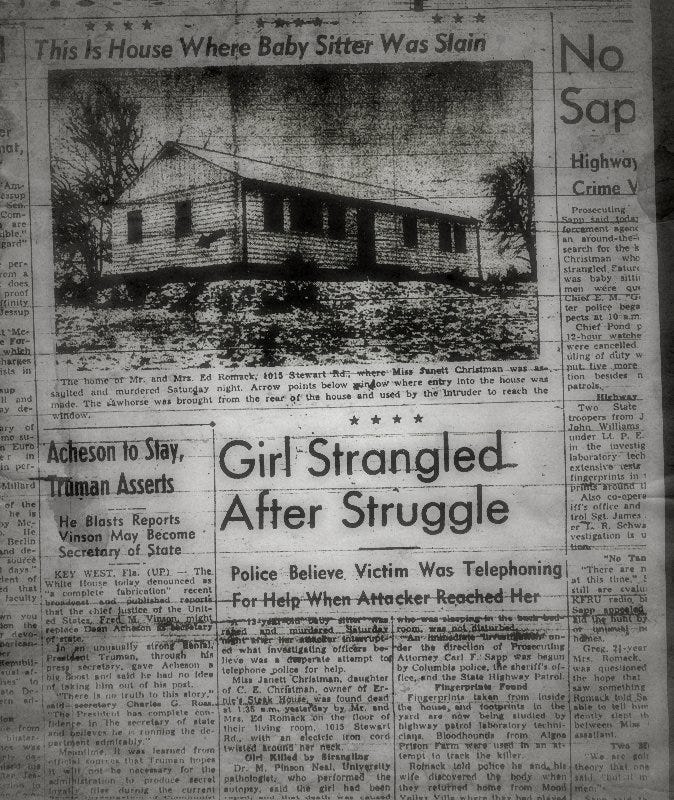

Our investigation now centers on Columbia, Missouri, on the night of Saturday, March 18, 1950.

The evening started with a scene of profound normalcy. A thirteen-year-old girl, Janett Christman, was babysitting for the Romack family, watching their three-year-old son. She was a responsible eighth-grader. The house was quiet, the child asleep. It was a picture of a safe and simple world.

The first indication that something had gone terribly wrong came not from a sound inside the house, but from a desperate signal sent out of it. The archives of the Columbia Daily Tribune contain the report: a local telephone operator, Jean Smith, logged a call from the Romack residence late that night. When she answered, she wasn’t met with a voice asking for help.

All she heard was a single piercing female scream. Then the line went dead.

Hours later, around 1:30 in the morning, the Romacks returned. The first sign that something was off was the front door—it was unlocked. A small detail, but one that plants a seed of dread. They stepped inside, expecting the familiar quiet of a sleeping house. Instead, they were met with a heavy, unnatural silence.

The living room was destroyed. This wasn’t just a mess; it was the physical record of a desperate, violent struggle. A heavy floor lamp was on its side, its shade crumpled. Furniture was thrown about. It was there, in the chaos, that they found Janett. She had been assaulted and strangled to death with the cord from a steam iron.

The police investigation painted a chilling picture of the killer’s method. He hadn’t used brute force. He had been patient. He found a ladder in the family’s garage, propped it against the side of the house, and carefully sliced a window screen to slip inside.

He had used their own tools to violate their sanctuary.

The crime horrified the town, but the trail went cold, and no one was ever charged. It became another heartbreaking, unsolved file in a cabinet.

But it’s one single detail from that crime scene, one object noted in the dry, technical language of the police report, that elevates this from a tragic cold case to something else entirely. It’s the detail that makes it seem like we’re looking at the original broadcast of the nightmare itself.

It was the telephone. After the fight, after the murder, after the scream on the open line, police found the telephone receiver. It wasn’t in its cradle. It was just hanging there by its coiled cord, a silent testament to a call that was never completed.

The events of that night in 1950 don’t just echo the famous story; they are the story. It feels less like a coincidence and more like a ghost print left at a crime scene. The terror that would go on to haunt millions wasn’t born from imagination. It was born in the violence of that living room, a perfect, horrifying sequence of events that was simply waiting for the rest of the world to hear about it.

The Ghost in the Machine: The Legend in the Digital Age

By all rights, this story should be a fossil.

Think about the engine that makes the whole nightmare run. It depends completely on a world that doesn’t exist anymore. You need a telephone physically chained to a wall. You need a killer whose identity is a total mystery because his number is untraceable. You even need a third party, a switchboard operator, to act as a detective and pinpoint the source of the call.

Take away any one of those pieces, and the entire terrifying machine should seize up and fall apart. The invention of Caller ID alone should have been a silver bullet, the equivalent of flipping on the lights and finding the monster was never there.

And yet, it’s not dead. The story is still here, and it’s arguably more effective than ever. So, how does a ghost born in an analog world learn to haunt a digital one?

It adapts. The narrative proved to be a master of evolution, shedding its old skin to find new and more efficient ways to get under ours.

Hollywood gave us the perfect proof-of-concept with the 2006 remake of When a Stranger Calls. The filmmakers knew the original premise was a non-starter in the 21st century. Their solution was chilling. The killer doesn’t just call the babysitter’s cell; he starts sending her pictures he’s taking of her in real-time, from inside the house.

Instantly, the phone transforms into a surveillance tool and a tracking device. The very thing that’s supposed to keep you connected becomes the ultimate proof of your isolation.

The story just updated its operating system. The hardware changed, but the malicious code is exactly the same.

This is the key to its survival. The terror was always rooted in the brutal violation of a safe space. The technology was just the delivery system for the primal fear.

In the 1970s, the delivery system was a copper wire. Today, it’s a Wi-Fi signal, a GPS locator, a network of smart home cameras that can be turned against you. The story is still so terrifying because we’ve willingly filled our home with a thousand new, more efficient ways for the call to come from inside the house.

The Echo in the Wires

It’s easy to dismiss a story like this. It’s a campfire tale, a thing of whispers and shadows that should fade in the morning light. But this one doesn’t. It holds on with a chilling persistence, and after digging through the archives, the reason seems terrifyingly clear. The story feels real because, at its core, it might just be a memory.

The brutal, unsolved murder of Janett Christman in 1950 serves as the story’s ghost print. The details of that night are a perfect, horrifying match for the narrative that would later sweep the nation. It feels like we’ve found the original, real-world broadcast of a nightmare that a later crime would only echo.

That’s where the story came from. But the real mystery is why it has never left us.

Its enduring power transcends the technology of a bygone era. It serves a single brutal function: to dismantle the most sacred belief we have—the idea that we are safe in our own homes. It’s a mechanism designed to find that one foundational sense of security and shatter it.

It exists to whisper a single, terrifying truth: the locks on your doors don’t matter when the monster is already inside.

That fear is primal. It’s timeless. It’s why the story has survived the death of the very technology it was built on, adapting effortlessly from the landline to the smartphone to the hacked security camera. The delivery system is irrelevant.

The story is a dark mirror, reflecting our own vulnerability back at us. And its message remains as effective today as it was in 1950. The call never disconnects. It just waits for us to answer.

Enjoying the investigation? Share this post with a friend who loves a good mystery.

To unlock our full archive of deep dives, join exclusive conversations in the comments, and get access to bonus case file materials, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support makes this work possible.

Reference

Bell, C. (2019). Terror by telephone: Normative anxieties around obscene calls in the 1960s. First Monday, 24(7). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/9463/8051

Brunvand, J. H. (1981). The vanishing hitchhiker: American urban legends and their meanings. W. W. Norton & Company.

Castle of Frankenstein Magazine. (1964). Issue #4.

Children and Youth in History. (n.d.). Baby sitter and the man upstairs [Urban legend]. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://chnm.gmu.edu/cyh/items/show/195

Clark, B. (Director). (1974). Black Christmas [Film]. Warner Bros.

Columbia Daily Tribune. (1950, March 19-25). [Various articles covering the Janett Christman murder investigation].

A Crime to Remember. (2018). Guess Who? (Season 5, Episode 6). [TV series episode]. Investigation Discovery.

Dear Abby Column. (1960s). [Various syndicated newspaper columns].

Dickey, C. (2016). Ghostland: An American history in haunted places. Viking.

Dundes, A. (1991). The babysitter and the man upstairs: A case study in the analytic method. In Interpreting Folklore (pp. 37–53). Indiana University Press.

Fischer, C. S. (1992). America calling: A social history of the telephone to 1940. University of California Press.

Griggs, A. R. (2012). The unsolved murder of Janett Christman: A historical and genealogical perspective. Legacy Books.

Hadena, J. (2019, January 14). An urban legend from Columbia, Missouri is known worldwide. Wordpress.

La Crosse Tribune. (1953, October 28). The disappearance of Evelyn Hartley. [Newspaper article].

Linic, C. (2017, October 13). The truth behind ‘the babysitter & the man upstairs’ urban legend. Medium.

Mikkelson, D. (1999, March 28). The babysitter and the man upstairs. Snopes. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/the-babysitter-and-the-man-upstairs/

Missouri State Archives. (1950). State of Missouri vs. [Redacted] [Archival police reports and witness statements regarding the Janett Christman case].

Radford, B. (2017). The enduring appeal of the ‘babysitter and the man upstairs’ urban legend. Skeptical Inquirer, 41(4), 48–51.

Schwartz, A. (1981). Scary stories to tell in the dark. Harper & Row.

Shipley, T. (2018, December 19). The history of caller ID: Progression of trust & distrust. CallerID Reputation.

Tolbert, J. (2015, October 1). Who killed Janett Christman? Inside Columbia.

Walton, F. (Director). (1979). When a stranger calls [Film]. Columbia Pictures.

Walton, F. (Director). (2017). The motive for murder: An interview with Fred Walton [Video interview]. Scream Factory.

Wikipedia. (2024). The babysitter and the man upstairs. Wikimedia Foundation. Retrieved October 13, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_babysitter_and_the_man_upstairs

Zeman, J. (Director). (2014). Killer legends [Film]. Chiller Films.

This was absolutely fascinating! I loved how you mapped the legend (and sad truths) across time and genres, and the sources are really interesting too. I can't wait to read more!

Great post! I've seen Killer Legends, which I liked, but didn't know the other stories.