The Ghosts of Portlock: Did a Killer Bigfoot Create an Alaskan Ghost Town?

Terror stalked Portlock in the 1940s. By the early 1950s, the town was gone. Was it a killer cryptid or economic collapse? The mystery endures.

Most American ghost towns died of natural causes. Gold veins ran dry, company funds evaporated, and railroads chose other paths. Their deaths were slow, predictable, and economic.

But Portlock, Alaska, didn’t just die. It was killed.

For years, this was a real, working town on the edge of the Kenai Peninsula, complete with a salmon cannery and a US Post Office. It was a community of families, fishermen, and loggers, clinging to the edge of a vast wilderness. Then, in the 1940s, something emerged from the woods.

A large, hairy creature—a beast that would later be known as the Nantiinaq—began stalking the community. It wasn’t a fleeting shadow; it was a visible threat. Hunters went into the hills and never came back. The mutilated bodies of residents were found washed up in the lagoon, torn apart in ways that defied explanation by bear or wolf attacks. The terror was so intense that the entire population fled in fear. They abandoned their homes, their jobs, and their way of life, and by 1951, the post office was officially closed. Portlock was deserted.

Two stories explain this disappearance. One is a harrowing account of survival, passed down by the last residents who swear they were hunted from their homes by a monster. The other is a tidy, official record of economic decline and population shifts. So, which is the truth? Did a monster erase an American town from the map, or is the official story missing a few bloody pages?

The Legend of the Nantiinaq

The Genesis of Fear

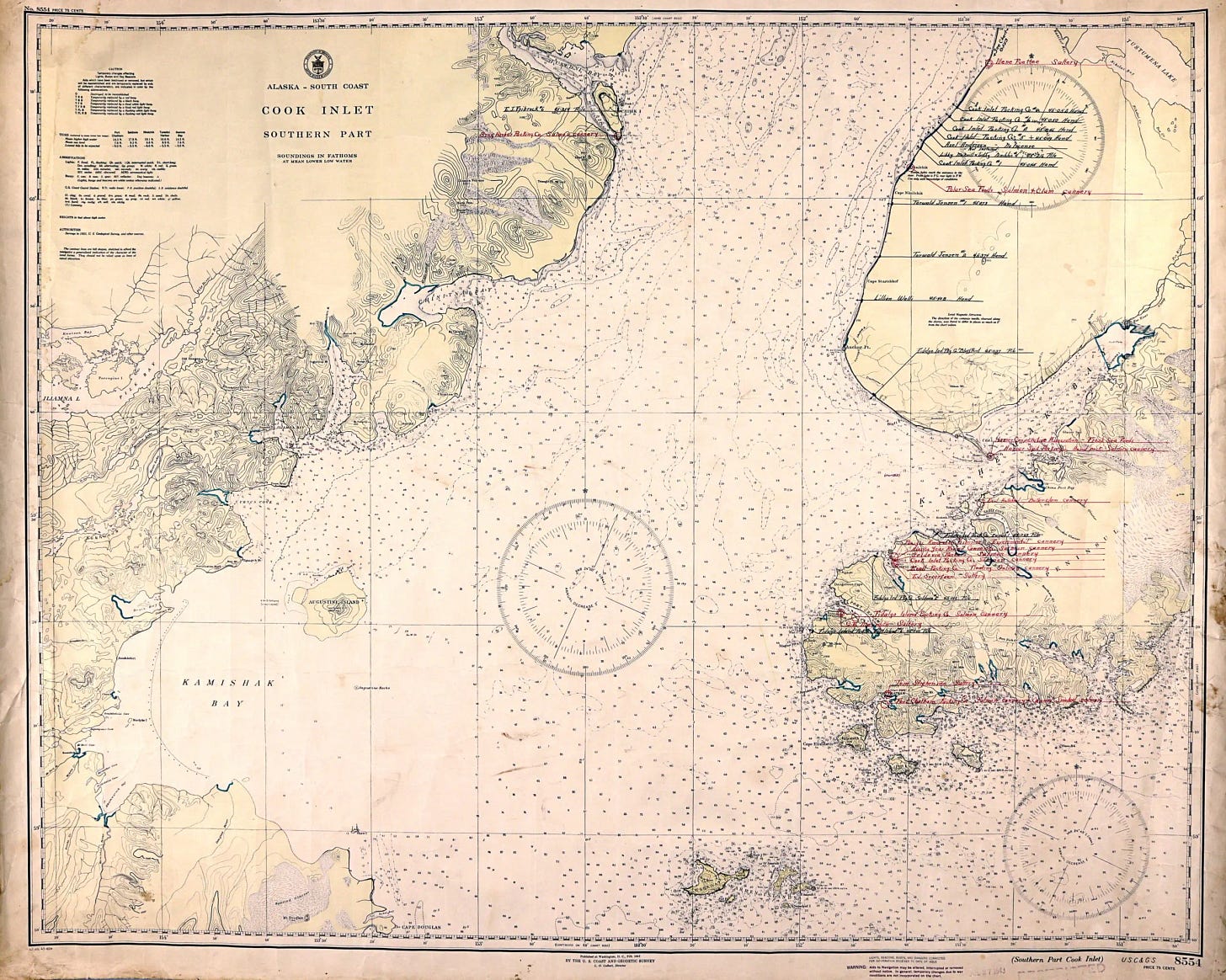

Every case file begins with a location, and in this story, the setting is as much a character as any person or creature. Portlock wasn’t a myth. It was a real, officially recognized American town with a US Post Office that opened in 1921. It was built in Port Chatham Bay, a remote spot on the southern tip of the Kenai Peninsula.

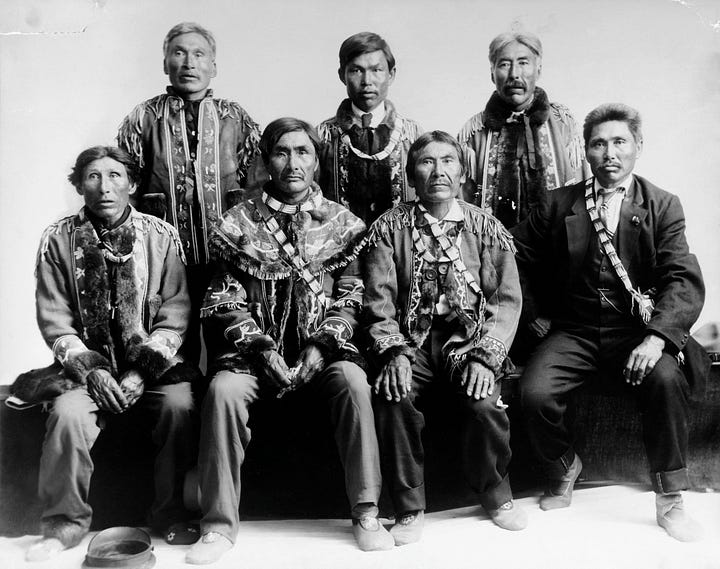

The town’s lifeblood was its salmon cannery, the economic engine that shaped a community from the wilderness. It was built on the traditional homeland of the Sugpiaq/Alutiiq people, and many residents were direct descendants of those who had lived there for millennia. But it was a town on an island, both literally and figuratively. With no roads linking it to the outside world, the dense spruce forest and cold grey sea formed its boundaries. This deep isolation meant that when problems arose, the people of Portlock were on their own.

The First Whispers & First Blood

The violent events of the 1940s weren’t the beginning. Unexplained occurrences in Portlock have been reported for decades, with the first unusual sightings dating back to as early as 1905. That year, cannery workers - men who were no strangers to the dangers of the wilderness - were reportedly “bothered” by something large in the woods. The historical accounts don’t specify what this disturbance entailed. Was it a figure seen at the treeline? Strange calls in the night? Or was it simply the unnerving, primal feeling of being watched by an unseen predator? Whatever it was, it was terrifying enough to prompt seasoned laborers to abandon their jobs and paychecks for the entire season.

The unease was compounded by other unexplained events. In the nearby village of Port Graham, an elder named Simeon Kvasnikoff would later recount the story of a gold miner who vanished near the area. The man went into the hills to prospect and was never seen again, his disappearance becoming another unsettling tale whispered among the small, isolated communities.

For years, these incidents remained disconnected whispers. Then, in 1931, the whispers became a scream.

A local logger named Andrew Kamluck was working in the dense forest around the bay. Hand-logging in the Alaskan bush was brutally tough and isolating work. When Kamluck was found dead, the nature of his injuries sent a shockwave of fear through the community. He was killed by a single, powerful blow to the head. The weapon, according to those who discovered him, was a piece of heavy logging equipment. In a place where men understood the tools of the trade, this detail was horrifying. They were aware of the weight and leverage of such an object. The strength needed to wield it as a weapon was considered beyond the ability of any normal man.

Kamluck’s death was a turning point. The vague fear that had lingered for years now had a body count. The assailant wasn’t a bear or a human foe; the evidence pointed to something else entirely - a silent killer with inhuman strength, hiding just out of sight in the endless forest.

Portrait of a Predator: The Creature of Portlock

Physical Features: The “Half-Man, Half-Beast”

The most tangible evidence the creature left behind was its footprints. In the mud and snow around Portlock, residents found massive, human-like tracks measuring a staggering 18 inches in length. The tracks pointed to a bipedal giant, a creature that walked like a man but possessed immense size and weight.

Those who saw it described a large, hairy being. But it was more than just an ape-like animal. The name that became synonymous with the creature, Nantiinaq, was translated from the Alutiiq language by elder Malania Kehl as “half-man, half-beast.” This unsettling description defined the terror; it wasn’t just an animal they were facing, but a monstrous hybrid of human and something else.

Aggressive Nature: A Pattern of Violence

The creature’s aggression was methodical and escalated over time. It began with attacks on the town’s livelihood, destroying fish wheels that were vital for processing salmon. This was a direct assault on the community’s ability to survive.

Its physical power was undeniable. It possessed the strength to wield heavy logging equipment as a weapon, as was evident in the death of Andrew Kamluck. This inhuman strength was a key reason it wasn’t mistaken for a human assault.

From property damage, the violence escalated to direct attacks on the people themselves. Numerous hunters and loggers who ventured into the hills surrounding Portlock disappeared, their disappearances attributed to the creature. The most horrific events were the discoveries of human bodies, reportedly washed into the lagoon from the mountains. These remains were torn and dismembered in a way that experienced woodsmen and hunters didn’t believe could be the work of a bear or any other known local predator. This pattern of escalating, brutal violence is why many who witnessed its work dispensed with formal names and simply called it a “devil.”

A Reign of Terror: The 1940s

The death of Andrew Kamluck in 1931 had been a shock, a brutal anomaly that left the town on edge. For nearly a decade, a tense quiet settled over Portlock. But the 1940s brought a new, horrifying chapter. The creature’s aggression intensified, shifting from isolated incidents to a full-blown campaign of terror that ultimately broke the community’s will to survive.

The harassment grew relentless. The menacing stares from the edge of the forest occurred daily. At night, work camps were “bothered” and harassed. The massive, 18-inch footprints appeared more often, serving as a constant reminder of the giant among them. The creature started to directly disrupt the town’s ability to function, at one point destroying the community’s fish wheels, which were vital for processing salmon.

Then, people started to disappear. Hunters and loggers who ventured into the surrounding hills, men who knew the land and its dangers, would simply vanish without a trace. Each disappearance sent a fresh wave of fear through the small community. The wilderness that had been their provider was now the hunting ground of a predator, and leaving the perceived safety of the village became a life-or-death decision.

The final, soul-crushing blows came when the missing were found. Bodies began to wash into the lagoon, carried down from the mountains. They were mutilated, torn and dismembered in ways that horrified even the most experienced woodsmen. These men, who understood the work of bears and wolves, insisted that no known animal could have inflicted such damage. This was the work of something else.

Faced with an enemy they couldn’t understand and couldn’t fight, the people of Portlock reached a breaking point. Living in a constant state of siege, watching their friends and family vanish, was no longer sustainable. They made an unthinkable choice: they abandoned their homes. In a gradual but final exodus, the entire town fled. The postmaster was the last to leave, officially closing the US Post Office between 1950 and 1951, forever erasing the town of Portlock from the map.

Investigating the Mundane

And now, we open a different file. For every chilling story of a monster, there’s a public record, a paper trail of economics, census data, and infrastructure projects. The official history of Portlock’s demise tells a story with no monster, but with a powerful and definitive conclusion all its own. To be thorough investigators, we have to examine it with the same critical eye.

The Official Story: An Economic Exodus

The primary driver behind Portlock’s abandonment, according to historical and economic records, wasn’t a creature from the woods, but a far more mundane monster: a collapsed economy. Portlock was, at its core, a cannery town, and its entire existence was tied to the health of the Alaskan salmon fishery. In the post-World War II era, that fishery was in a state of catastrophic crisis.

Decades of poor federal management and systematic overfishing, driven by the widespread use of hyper-efficient fish traps, had decimated salmon runs across the territory. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, the industry was considered a federal disaster. This rendered many small, remote canneries like the one at Portlock completely unprofitable. The closure of the Portlock cannery wasn’t a unique event driven by fear; it was part of a widespread, predictable pattern of cannery failures across Alaska during this period.

This first blow was followed by a second. At the same time, the fishing industry was collapsing, the new Alaska highway system, specifically Alaska Route 1 (the Sterling Highway) on the Kenai Peninsula, was creating a new economic artery. Towns connected to the highway boomed, while remote, water-access-only communities like Portlock were left increasingly isolated and economically unviable.

According to this data, residents left Portlock not in a single, panicked flight, but in a gradual, practical relocation to places with more opportunities, such as the nearby villages of Nanwalek and Port Graham. The official end of the community, marked by the post office closure between 1950 and 1951, aligns perfectly with this timeline of economic collapse.

The Archival Silence: A Story With Two Meanings

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence in this investigation is what the historical record doesn’t say. Researchers have conducted exhaustive searches of Alaskan newspaper archives from the 1930s and 40s and have found no contemporary articles mentioning a reign of terror in Portlock. There are no reports of mutilated bodies, no stories of a panicked exodus, and no mention of a creature.

This silence is particularly loud regarding the 1931 death of logger Andrew Kamluck. While his death is a cornerstone of the Natiinaq story, official records state his death was an accident. Furthermore, US Census records show his family was living in Portlock nine years later, which challenges the idea that his death caused immediate, mortal fear.

On its face, this “archival silence” appears to be a compelling argument that the terrifying events were a later invention. However, this is Alaska, and things are rarely that simple.

Alaska has the highest rate of missing persons per capita in the United States, a rate that is more than double the national average. Thousands of people have vanished into its vast wilderness over the years, often without leaving a trace. The rugged terrain, extreme weather, millions of acres of dense wilderness, and dangerous wildlife mean that people can, and do, disappear without generating a single official report or news story.

In the 1930s and 40s, Alaska was a sparsely populated territory with limited communication and law enforcement infrastructure. It’s plausible that deaths or disappearances in a remote, boat-access-only village like Portlock might not have been widely reported, especially if they were attributed to the known dangers of the Alaskan wild.

This leaves us with a difficult question. Is the archival silence proof that the attacks never happened? Or does it simply reflect the harsh reality of a time and place where people could vanish into the wilderness without leaving a single trace in the official record?

From Memory to Modern Legend

If the story of the Nantiinaq wasn’t in the newspapers of the 1940s, where did it come from? The paper trail of the story itself is much more recent, which adds another layer of complexity to the investigation.

The events supposedly happened between the 1930s and the early 1950s, but there is a significant time gap before the story appears in print. The first known public mention dates to a 1973 article in the Anchorage Daily News. The article, documented by cryptozoologist Loren Coleman, was based on the decades-old recollections of a retired school teacher who had been in the area.

For decades, the story remained a piece of obscure local folklore. It was truly ignited in 2009 by an article in the Homer Tribune that featured the detailed, terrifying oral history of elder Malania Kehl. This article became the foundational text for the modern Portlock legend, spreading rapidly across paranormal websites and forums.

A key point to analyze is the name of the creature itself: “Nantiinaq.” Linguistic research shows this isn’t a word from the local Sugpiaq/Alutiiq language spoken in Portlock. The term seems to be a borrowed word from the Dena’ina, a different Indigenous group, where nant’iana refers to a folkloric “bogeyman” used to scare children. The local Sugpiaq people have their own word for a Bigfoot-like creature, arularaq.

This brings us to a final, tough question. Does this timeline—a 30-year gap before the first mention and a recent surge in popularity—prove the story is a modern invention, a piece of what folklorists call “fakelore”? Or were these journalists and storytellers simply the first to publicly record a real, traumatic oral history that had been kept private by a community too frightened to speak of it earlier?

A Tale of Two Porlocks

In the end, we’re left with two distinct stories, each compelling, and each demanding that we disregard the other. They exist side-by-side, a paradox of history and horror.

The first story is the one carried out by the people who fled. It’s a harrowing tale of a community under siege by an unknown predator. It’s a story of strange deaths, unexplained disappearances, and mutilated bodies - a story that ends with an entire town abandoning their homes to escape a monster with inhuman strength. It’s a story preserved not on paper, but in the traumatic memories of those who swear they lived it.

The second story is the one told by the official record. It’s a clear, logical account of economic cause and effect. A key industry collapsed, a new highway rerouted trade, and an isolated town gradually and predictably faded away. This version is supported by a complete absence of contemporary news reports of violence and questions about the modern origins of the story itself. It’s tidy, reasonable, and fits well within the known facts of Alaskan history.

To believe the official record, you must conclude that the vivid, terrifying accounts of multiple residents are a shared delusion or a modern invention. You must believe the stories of bodies and disappearances are nothing more than campfire tales.

To believe the eyewitnesses, you must conclude that there is a chilling gap in the historical record. You must accept that a group of people could be hunted from their homes by a real, breathing cryptid, and the outside world would simply not notice.

So, what do you believe happened in the remote wilderness of Portlock? Is it a ghost town haunted only by the memory of a lost way of life, its history embellished by a modern myth?

Or do its silent, crumbling ruins stand as a monument to the victims of an unknown creature that, perhaps, still roams the deep woods of Alaska?

References

Alaska Historical Society. (n.d.). Alaska salmon cannery chronology. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://alaskahistoricalsociety.org/about-ahs/special-projects/alaska-historic-canneries-initiative/alaska-salmon-cannery-chronology/

Alutiiq Museum. (n.d.-a). Alutiiq/Sugpiaq. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://alutiiqmuseum.org/alutiiq-people/

Alutiiq Museum. (n.d.-b). History. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://alutiiqmuseum.org/alutiiq-people/history/

Anchorage Public Library. (n.d.). Unangax̂ (Aleut) & Alutiiq/Sugpiaq. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://www.anchoragelibrary.org/resources/research/alaska-collection/research-guides/unangax-aleut-alutiiqsugpiaq/

Baxter, L. (2021). Abandoned: The history and horror of Port Chatham, Alaska. Alasquatch Publishing.

Boraas, A. (2014, August 20). The mythology of salmon. Peninsula Clarion. https://www.peninsulaclarion.com/life/the-mythology-of-salmon/

Chugach Heritage. (n.d.-a). Conservation lore. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://chugachheritageak.org/pdf/FFS_9-12_10-12 _Conservation_Lore_Final.pdf

Chugach Heritage. (n.d.-b). History of the Chugach people. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from http://chugachheritageak.org/resource-files/The_Chugach_Story.pdf

Chugach Heritage. (n.d.-c). What's in a name: The predicament of ethnonyms in the Sugpiaq-Alutiiq region of Alaska. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from http://chugachheritageak.org/resource-files/Whats_in_a_Name-The_Predicament_of_Ethnonyms_in_the_Sugpiaq-Alutiiq_Region_of_Alaska.pdf

Coolidge, C. (n.d.). A guide to monsters of Alaska. True North Magazine. https://www.truenorth-magazine.com/a-guide-to-monsters-of-alaska/

Crowell, A. L., & Mann, D. H. (1996). The history of Port Graham and Nanwalek. Project Jukebox, University of Alaska Fairbanks. https://jukebox.uaf.edu/node/4495

Csoba DeHass, M. (n.d.-a). Oral history. Nanwalek History. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://nanwalekhistory.com/oral-history/

Csoba DeHass, M. (n.d.-b). Sugpiaq ethnohistory. Nanwalek History. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://nanwalekhistory.com/about/

Dunning, B. (2021, March 23). The monster of Port Chatham. Skeptoid Podcast. https://skeptoid.com/episodes/4772

ExploreNorth. (n.d.). The history of Kenai, Alaska. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://www.explorenorth.com/library/communities/alaska/bl-Kenai.htm

Historic Mysteries. (2022, March 22). The Portlock Sasquatch: Terror in an abandoned Alaskan village. https://www.historicmysteries.com/unexplained-mysteries/portlock-sasquatch/23766/

Holtz, H. R. (2024, September 4). Portlock, the Alaska ghost town allegedly home to a 'killer bigfoot'. All That's Interesting.

Jackinsky, M. (2021, April 28). New book looks at legend of Alaska's 'Nantiinaq,' or 'giant hairy thing'. Homer News. https://www.homernews.com/life/new-book-looks-at-legend-of-alaskas-nantiinaq-or-giant-hairy-thing/

Judson, K. B. (1914). Myths and legends of Alaska. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47146/47146-h/47146-h.htm

Kasvinsky, H. (2024, September 24). The ghostly abandonment of Portlock, Alaska. Alaska Adventurers. https://alaskaadventurers.com/portlock-alaska/

Klouda, N. (2009, October). Something's afoot in Port Chatham: Century-old rumors persist of a terror in the mountains. Alaska Magazine. https://alaskamagazine.com/authentic-alaska/somethings-afoot-in-port-chatham-century-old-rumors-persist-of-a-terror-in-the-mountains/

National Park Service. (n.d.-a). The lost villages. Aleutian Islands World War II National Historic Area. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://www.nps.gov/aleu/learn/historyculture/lost-villages.htm

National Park Service. (n.d.-b). History of the Kenai Peninsula. NPS History. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://www.npshistory.com/publications/kefj/hrs/chap2.htm

Reger, R. D., Sturmann, A. G., Berg, E. E., & Burns, P. A. C. (2007). A guide to the late Quaternary history of northern and western Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys. https://dggs.alaska.gov/webpubs/dggs/gb/text/gb008.pdf

Seward, C. (2024, November 16). This abandoned ghost town in Alaska is downright bone chilling. OnlyInYourState. https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/experiences/alaska/this-abandoned-ghost-town-is-downright-bone-chilling-ak

State of Alaska, Department of Fish and Game. (n.d.). The history of upper Cook Inlet salmon fisheries. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm%3Fadfg%3Dwildlifenews.view_article%26articles_id%3D639

State of Alaska, Department of Fish and Game. (2012). The commercial salmon fishery in Alaska. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/home/library/pdfs/afrb/clarv12n1.pdf

State of Alaska, Department of Labor and Workforce Development. (2024, May). Three very different ghost towns. Alaska Economic Trends. https://live.laborstats.alaska.gov/sites/default/files/trends/may24art2_0.pdf

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Portlock, Alaska. Retrieved July 27, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portlock,_Alaska